[bleu]Text into French[/bleu]. [rouge]Clic on the pictures to enlarge[/rouge]

I am often invited to speak at conferences in monasteries and religious communities throughout Europe, and I have discovered on these occasions that some of them, while remaining faithful to the forms and traditions of the past (liturgy, monastic rule) are nonetheless very innovative when it comes to contemporary art and architecture.

One significant feature of this surprising mixture of tradition and modernity, or even post-modernity, is without doubt the intention to show that monasticism is not opposed to the modern world. On the contrary, it allows us to better understand the world, even as it emphasizes its limits. Another significant feature is the desire to go beyond a solely patrimonial vision of Christianity ; monks are not necessarily linked to the magnificent convents and monasteries dating to the Middle Ages, the Renaissance or the Baroque period that are scattered all over Europe, which, though they be artistic gems, are often remote from present-day life. Monks can also live in modern buildings. Our problem in Europe is quite the opposite of the one encountered in the U.S., for we have too many historic buildings, too many old churches, too much of... the Middle Ages !

A third intention in embracing contemporary art is to show that modern esthetic forms, being clean, sober and aniconic, convey in themselves an authentically Christian spirituality. Just as the God of the Bible is allusive and cannot be fixed in a shape or an object, likewise contemporary architecture sometimes conveys better than more classical forms the mystery, the living presence of God, the breath of the Holy Spirit.

I will demonstrate this through several examples that I have discovered and photographed myself. I have had to limit the choice to a representative selection and to three countries (France, Germany, Portugal), out of the many other examples that could be shown.

I have limited the scope to convents that are still inhabited at present by religious communities, but one could obviously make the same demonstration by using churches and cathedrals, in which another type of religious community gathers, namely the assembly believers and the baptized.

I would like to distinguish two different concepts in the connection between past and contemporary architectural forms. The first is traditional : modernism adds, often discretely, to existing forms, often to better showcase them. The second is more radical : modernism replaces, substitutes itself for, the existing forms. In the first case the artistic creation places high value on past history, whereas in the second case it takes its place. I will show you four examples of each of these two cases.

1. Adding contemporary forms to or alongside historical ones(continuity in creation)

– 1.1. The community of Benedictine Sisters of Maumont (Southwest France).

I have chosen purposefully to begin with this example, because it will be meaningful to the Community of Jesus. It is indeed a community of Benedictine sisters, whose convent is historic, but not very practical. The community subsists mainly through its bookbinding activity.

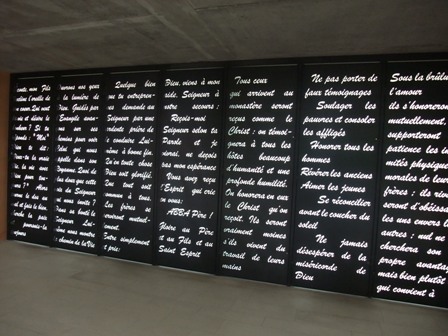

After Vatican II, and then at the beginning of the 21st century, the sisters decided to modernize the chapel, and also to renovate the convent’s entrance. In place of the iron grid work that had made its front look like a prison, there is now a superb gateway, made of letters and phrases cut out of flat iron plate. What do those letters say ? They recall the most important elements of the Rule of St. Benedict. Thus the visitor, even before entering the convent, can read its spiritual precepts, meditate on them and perhaps choose to enter into the community to meet and to pray with it. Because the letters have been cut out of iron plate, they let light penetrate, and when the sun is shining they can be read twice : in the empty space cut out of the gate, and projected as a shadow on the walls to each side.

– 1.2. The stained-glass windows of Soulages in the Abbey of Conques (Southwest France)

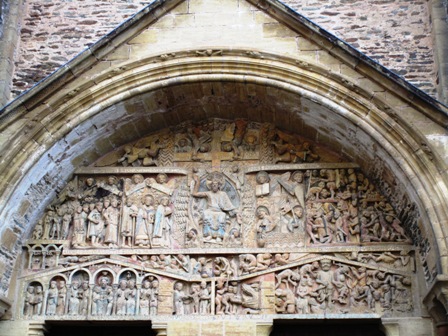

At times a building’s architecture is so famous that there can be no question of transforming it. On the contrary, it must be showcased. The famous Abbey church of Sainte-Foy in Conques (Southwest France) is known throughout the world as one of the gems of roman art (11th century), and is classified as a UNESCO world heritage site. Equally famous is its tympanum, sculpted in the 12th century, depicting the Last Judgment.

Hundreds of thousands of tourists come each year to visit it, but that does not prevent its small Augustinian community from living and praying there each day. In 1986 the French government asked the artist Pierre Soulages (born in 1919), the best-known French artist living at that time, to make new stained glass windows for the abbey. Rather than proposing figurative windows, which would probably have disrupted the visitor’s perception of the abbey’s medieval architecture, Soulages spent several years crafting translucent white glass for the abbey’s 95 windows, whose stained glass was composed only of this particular white color, cut by parallel black lines that echo the arches spanning the abbey’s nave . The particularity of these windows is that they reflect the light, and thus can be viewed from the outside as well as the inside.

Thus they highlight the strength of the roman architecture on the inside, while they also reflect the sky on the outside. Thus these non-figurative windows create an atmosphere of peace and contemplation which help to nurture reverence and prayer. Soulages himself said the following : “From the beginning I was inspired by the desire to serve this architecture such as it has come down to us, by respecting the purity of its lines and proportions, the shifting shades of its stone, the way its light is organized, the life that takes place in such a unique space. Far from attempting to reconstitute, imitate or rethink the Middle Ages, I tried to make use of the technologies of our day to produce glasswork that corresponds to the identity of this sacred building of the 11th century with its emotional and artistic powers.”

In the new Soulages museum (opened in 2014) located in the nearby city of Rodez – the artist’s birthplace – are displayed the 200 preliminary sketches of the 95 stained-glass windows of Conques.

– 1.3. The new chapel next to the Benedictine abbey of Ettal (Bavaria, Germany)

Another example of modern architecture built alongside a prestigious example of historic architecture, this time Baroque : in this case the Benedictine abbey of Ettal, in Upper Bavaria, Germany. Those who know the Lutheran theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer know that he spent several months in this abbey (from November 1940 to February 1941), before entering into the service of the Confessional Church, which opposed Hitler, and this led to his death as a martyr.

The interior of this church is superb. However the monks must have wanted to remind us that we are no longer living in the era of baroque art (the 17th and 18th centuries), for they recently built, on the eastern flank of the church, a small, modern chapel, constructed in concrete. The roof reminds us of a tent, in order to represent the fragility of the church in today’s times. A skylight reveals a rainbow, symbol of the Covenant between God and his people. The altar is made of sheets of translucid earthenware, in which the word “Light” is engraved in numerous languages, to represent the universality of Christianity, which is present on all 6 continents. Once again, as in Conques and in Maumont, we find a cohabitation of historic and modern art forms.

– [bleu]1.4. The church of the Junior Seminary in Braga, Portugal (2015)[/bleu]

[rouge]Clic here to have the pictures of the inside of Braga’s new church[/rouge]

A further step was taken with the church of the Junior Seminary in Braga, Portugal. The outside of the church (the capela imaculada), of a rather ordinary architectural style, was conserved. Inside, however, everything is new . We find an alliance of three elements, concrete, wood and light, which are disposed to facilitate prayer, and in view of the training and vocation of future priests. The visitor is surprised by the simplicity of the whole, in a country such as Portugal, in which, on the contrary, the interiors of churches generally feature a profusion of shapes, of gold, of sumptuous elements and rich decoration. In this renovated church, everything has been considered, everything is symbolic : not only its architecture, but also its interior layout, its light sources (both natural and artificial), its liturgical furnishings (under the altar there flows a fountain of running water). Natural gems take the place of stained-glass windows, letting in diffused light. On one of the benches is a human figure : a sculpture of Mary, the mother of Jesus, seated there as if she had come into the church to pray. A very human Mary, in all ways similar to us, thus a very Protestant Mary. The artist who sculpted her, the Norwegian Asbjorn Andresen, is indeed a Lutheran. This Protestant Mary is the only sculpture to be found in this Catholic church, built to serve future priests. Is this not a genuine case of ecumenism through art ?

The gallery is a more intimate space, built in wood and conceived for small-scale meditations based on two liturgical axes, namely the proclamation of the Word and the celebration of holy communion.

For the moment we have looked at modernizations of historic churches or modern additions to historic churches, in settings in which the churches serve for the prayer of monastic communities (or future priests in the case of Braga). In each of these cases, as in the two that we are about to discover, it was important to create an atmosphere of community, a place in which the worshipper feels in peace, or desires to remain in order to meditate, to pray, to listen to Scripture together, or to celebrate holy communion.

2. The construction of new monastic buildings (ex nihilo creations)

Other communities have made more radical choices, by building new churches or convents ex nihilo, from scratch. We will look at four examples :

– 2.1.The new monastery of the Clarisses (2011) below the church of Ronchamp, built by Le Corbusier (1955)

Le Corbusier (1887-1965) was one of the best-known architects of the 20th century. In 1955 he built the Catholic chapel of Notre Dame du Haut at Ronchamp, near Belfort, in the east of France, not far from both Switzerland and Germany. This chapel is without a doubt the most famous example of religious architecture from the 20th century . Today more than 100,000 tourists come to visit it each year. What is less well known is that Corbusier was raised in a strict Swiss Calvinist family, which undoubtedly explains his attraction for simple forms, empty spaces and harmonious proportions.

The success of this contemporary church has recently drawn a community of Clarisses, or Poor Clare Sisters, who decided to establish themselves at the foot of the hill, in order to better accompany the tourists and pilgrims it attracts. It began as a discrete but innovative architectural project, carried out between 2008 and 2011 by the famous Swiss-Italian architect, Renzo Piano : a horizontal, ecological monastery, which, planted as it is on the flank of the hill, is respectful of the landscape around it. Here is what the architect said on the subject : “We opened the hill, we put the sisters inside, and now nature, silence and prayer have reclaimed their rights” .

This religious community has established itself at the foot of the church of Ronchamp, thereby testifying to the fact the Le Corbusier’s church is not simply a remarkable architectural prowess, but a place of prayer, of silence and meditation. It attracts numerous tourists, but its vocation is to attract pilgrims, men and women in search of faith. This new, half-buried convent is sufficiently discrete so as not to throw a shadow on the prestigious architecture ; its role is to assist the chapel of Ronchamp in becoming once again a place of prayer, and inducing the tourists to become pilgrims.

– 2.2. The convent in La Tourette (1956-1960) by Le Corbusier (Lyon, France)

Just after completing the chapel at Ronchamp, Le Corbusier built a modern monastery : Saint Mary’s convent in La Tourette, near Lyon . He undertook the project at the request of the Dominican brothers, and in particular Father Alain-Marie Couturier, director of the periodical Art Sacré, which was in conversation with the greatest artists of the time (Picasso, Chagall, Léger, Braque, Matisse) . The Dominicans were convinced that Le Corbusier’s contemporary architecture corresponded to their spirituality. The convent, which was built between 1956 and 1960, is made of raw concrete, built on stilts, and consists of 5 floors.

The areas reserved for meditation (chapel) are closed spaces with skylights. Other areas reserved as meeting spaces (the refectory) are very well lit and open towards the outside. Since 2016 this convent, like all the rest of Le Corbusier’s constructions, has been classified as a UNESCO world heritage site. This building – or rather group of buildings – is shaped like an inverted pyramid, and is perfectly well integrated into its surroundings. It favors introspective meditation as well as community life. On the inside it is as if we were in an ocean liner, sailing the seas. We feel protected and safe. Le Corbusier said the following about his construction : “This convent built of rough concrete is a work of love. It doesn’t speak. It is experienced, from the inside of our being. The essential takes place on the inside” .

– 2.3. Convent of the Dominican sisters of St. Matthew of Treviers, (Southwest France)

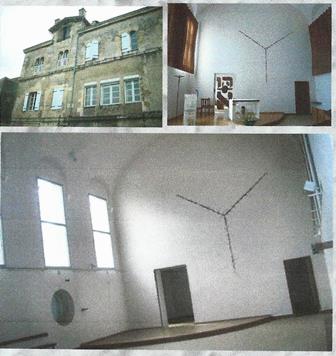

This convent, modern and of modest proportions, is located in the south of France, near Montpellier (St-Matthieu de Treviers). It is the convent de la transfiguration, which is home to Dominican, and was built between 1971 and 1976. The convent and the chapel were designed by a famous artist, Thomas Gleb (1912-1991), a Jew who fled Poland during the war and who, while he did not convert to Christianity, became closely connected to it. In 1932, in Paris, he changed his name, Yehouda Chaim Kalman, to Thomas Gleb :“Thomas, because I had not believed” .

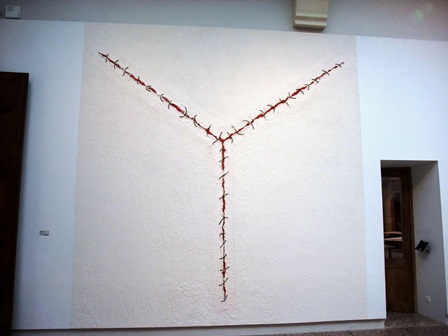

Thomas Gleb completed a work of art entitled "The sign" (1979). It is a monumental work (3.70 meters in height) cut into the wall, in the shape of a “Y”. It was created for the former Carmel of Niort, and should have disappeared as a result of a renovation project that transformed the chapel into a loft. The director of the Hiéron Museum in Paray-le-Monial, Dominique Dendraël, succeeded in saving this sign by having it removed from the wall in which it was embedded and displaying it in her museum. The sign has a threefold meaning : the “Y”, is at once the first letter of YHWH (the divine Name that cannot be pronounced), and of Yeshoua (which is Jesus in Hebrew), and also of Yehouda, the artist’s Jewish first name. This “Y” is blood red in color, like a wound, and it is criss-crossed by thin cords that resemble stitches closing a wound. It therefore represents a scar, which evokes a deep wound. Three other symbolic references are present in connection with this wound : an allusion to the life story of the artist who escaped from the Shoa, and more generally to the dramatic history of the Jewish people in the 20th century, but also (since the wound has been closed) to the possibility of reconciliation between Judaism and Christianity.

What is more, we find this sign, this “Y”, in the architecture of the chapel of St. Matthew’s Convent in Treviers. This chapel is round in shape, sober in its style, and its light source, which penetrates windows that are partly obscured, helps to foster the community’s meditation and worship.

– 2.4. The chapel of the Protestant Deaconesses of Versailles, France (2008)

The last example is of a radically new architectural form within a Protestant religious community, which is very rare case. It is the community of deaconesses in Reuilly (Paris), whose motherhouse is located in Versailles. Rather than enlarging their former chapel, which was of modest proportions and lacking in any particular artistic qualities, the sisters decided to undertake a modern construction that would be at once economical, ecological and esthetically pleasing.

The new chapel, designed and built by the Lutheran architect Marc Rolinet, and inaugurated in 2008, is based on two antithetical principles : a glass patio, in the shape of an ascending triangle, similar to the prow of a boat. It is a space that allows the visitor to communicate with the outside, to contemplate the magnificent grounds in which the chapel is situated . This glass structure encloses (or protects) the space designated as the place of worship, and thus the logic has been inverted : it encloses itself.

Like the hull of a boat that has been turned upside down (or half of an eggshell), it focuses our sight towards the interior, since there is no opening. This protective shell is made of strips of pinewood that were strapped into place, one by one.

One might add to the description of this almost futuristic construction, that of the pavilion of the novices, which was designed by the same architect several years earlier. He set the building on stilts, which gives it the advantage of taking up less ground space. In addition, it emphasizes the building’s shape, which is that of an open book (the Bible). Thus the technical constraints of such a construction have been made subservient to the symbolic shape of the building.

I hope I have demonstrated three things through the variety of these examples :

1. Architectural shapes, be they traditional, modern or postmodern, play a role in the worship life of the community. That is why these communities pay particular attention to the architectural and artistic choices that they make.

2. The old and the new are not opposed to one another, and indeed can be useful complements one to another. When modernity makes a tabula rasa of all that has come before, following the radical formula of ex nihilo, it is often because there is too much of the old : in such cases the objective is to show that Christianity is not a religion of the past, but of the present and even the future.

3. Finally architecture - be it traditional or modern – represents a complete artistic language. Not only because it comprises other forms of artistic creation (stained-glass windows, liturgical furniture, paintings, sculpture), but also because architecture can be approached both from the outside and the inside. It is an art form in which we can live, both literally and figuratively.

(Translation into English : Wendy Pradels)

J. Cottin